Goethe's Chamber

Every act of seeing leads to consideration, consideration to reflection, reflection to combination, and thus it may be said that in every attentive look on nature we already theorize. —J. W. Goethe

Goethe’s Chamber is a group exhibition that invites visitors to reconsider vision as an embodied, subjective and durational experience, continuously augmented by emergent technologies and theorized from various vantages throughout the ages. Located at the intersection of science and fiction, the exhibition’s title is an allusion to polymath Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s pioneering work The Theory of Colour (1810). Rather than offering a cohesive doctrine, Goethe’s study attempts to reverse previous accounts of optical experience with a catalogue of vividly described phenomena produced via his experimentation with color, shadow and light. While the scientific veracity of some of Goethe’s claims was subsequently challenged, the work marks a turning point in the evolving conception of vision, and deeply influenced vanguard colorists such as J. M. W. Turner and Vasily Kandinsky. As the scholar Jonathan Crary observes, “It is a moment when the visible escapes from the timeless incorporeal order of the camera obscura and becomes lodged in another apparatus, within the unstable physiology and temporality of the human body.” Assembling a diverse group of established artists whose inventive practices—their own experiments with shadow and light—reinvigorate their chosen media, Goethe’s Chamber encourages visitors to become active participants in the phenomenological encounters staged by each of the artworks on view.

Linda Connor | Known for her peripatetic practice and exquisite prints, Bay Area photographer Linda Connor (b. 1944, New York, NY) turns her gaze skyward in a project she started in the late 1990s: making prints from the glass plates housed in the archives of the Lick Observatory—the world’s first permanently occupied mountaintop observatory, constructed just east of San Jose between 1876 and 1887. E. E. Barnard once used the Lick Observatory to make “exquisite photographs of comets and nebulae,” as well as eclipses and other celestial phenomenon that took place hundreds of millennia ago; these images (and others like them) became the subject of Connor’s remarkable series. In addition to a constellation of small-scale contact prints on printing out paper, Connor also presents three new larger works based on the Lick’s plates—shimmering sublimation prints made directly on aluminum. As the critic Mark Alice Durant wrote of the work, “Reapplying the appropriate nineteenth-century photographic process to the Lick’s glass plates, Connor resuscitates the ghostly traces of stars whose photographic glow began eons before the dawn of human History.”

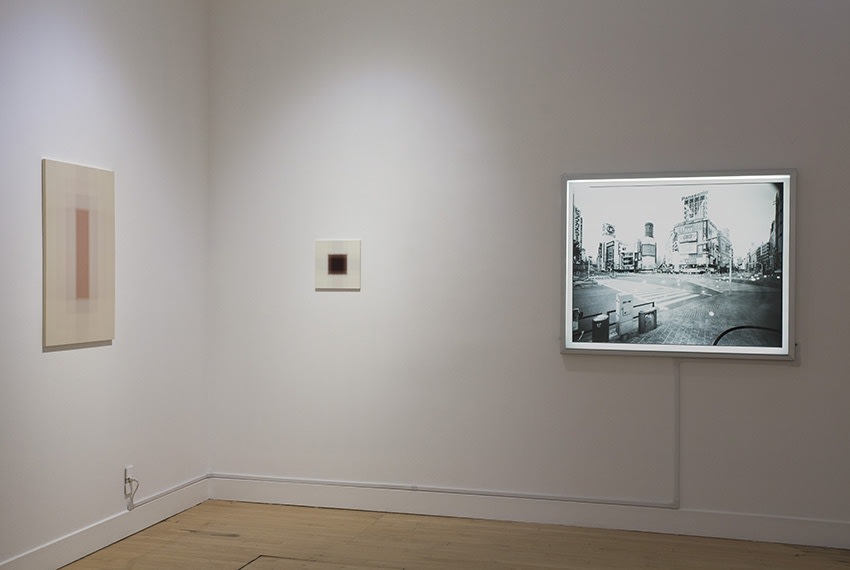

Patsy Krebs | The latent geometric forms nested within Patsy Krebs’ (b. 1940; lives and works in Inverness, CA and Colorado Springs, CO) Ovum series (1998–1999) underscore the durational aspect of seeing, floating into focus only after a period of concentrated, sustained viewing. At once completely abstract and highly representational, each of the small paintings in this body of work is an exact rendering of the surface a particular bird’s egg: the Brewer’s Sparrow, the Hermit Thrush and the Ruby-Throated Hummingbird, among them. These delicate paintings at first appear monochromatic before giving way to more complex and textured surfaces that ultimately reveal rectilinear forms.

Won Ju Lim |The diverse artistic output of Los Angeles-based artist Won Ju Lim (b. 1968, Gwangju, Korea), which includes multimedia installations, sculptures and wall-hung works, invites audiences to reconsider the built environment and its relation to memory, fantasy and longing. Lim’s formally inventive, research-driven practice draws from sources that include baroque architecture, fantasy and science fiction films, and the urban landscape. Her new Kiss pieces, shown at Haines Gallery for the first time—wall-hung, box-like sculptures that offer a knowing nod to Judd’s Stacks—produce colorful cascades of geometrical shadows when light passes through them. The sculptural components within are Plexiglas architectural models based on plans of the famed Case Study Houses—quintessential examples of mid-century modernism built in the Los Angeles area between 1948 and 1966. Such models are frequent building block in Lim’s work, is both a sculptural component offered for aesthetic consideration and a provisional reference point for an idealized elsewhere.

David Maisel | Traveling across the electromagnetic spectrum, Bay Area photographer David Maisel’s (b. 1961, New York, NY) ongoing series History’s Shadow—initiated while he was a scholar-in-residence at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles in 2007—is derived from X-rays of antiquities found in the conservation departments of the Getty and the San Francisco Asian Art Museum. Used by art conservators for structural examination of art and artifacts in the same way that physicians examine bones and internal organs, the X-rays reveal losses, replacements, construction methods and internal trauma invisible to the naked eye. By illuminating and re-photographing his source material— images of ceremonial vessels, ancient statuary—Maisel superimposes both the inner and outer surfaces of his subjects, forging spectral images that seem like transmissions from the distant past, both spanning and collapsing time.

Tokihiro Sato | Tokyo-based artist Tokihiro Sato’s (b. 1957, Yamagata Prefecture, Japan) phantasmagoric black-and-white images of empty urban streets, rice fields and forests are punctuated with dazzling points of light that seem to materialize from some supernatural source. Using a large-format camera fitted with a darkening filter, Sato deploys exposures of up to two hours, during which time, he moves through the landscape, pausing periodically with a mirror to reflect sunlight back at the camera. Because Sato remains in slow but constant motion throughout the long exposures, he is invisible in the photographs. Sato’s photographs are presented as backlit transparencies—a format that underlines the role of light in the image. “The light becomes volume,” Saito observes, “while the light traces I make as I move around represent the passage of time, creating a sculpture in space.”

David Simpson | To create his astounding paintings, David Simpson (b. 1928, lives and works in Berkeley, CA) employs interference pigments, offering viewers a pyrotechnic display of shifting colors that shimmer to the surface as one passes before them. Unlike more traditional pigments, which absorb white light and reflect back a single wavelength of color, interference pigments consist of layers of various metal oxides deposited onto mica, a natural mineral. Light striking the surface of these pigments is refracted, reflected and scattered by the layers that make up the pigment. Through a carefully calculated superimposition (or interference) of the reflected rays of light, Simpson conjures the play of contrasting and complimentary colors by applying up to thirty layers of paint to the canvas. The colors produced by interference are dependent on the angle of observation and illumination.